Written by James Postema, professor of English and principal investigator of the Concordia College – Moorhead, MN, Crafting Democratic Futures team

Project Description

At Concordia, we believe that the most distinctive contribution we can make to the Crafting Democratic Futures project is to focus on research and restorative action for Native American people in our home community of Fargo (North Dakota) and Moorhead (Minnesota), cities in two different states with a common border along the Red River. Concordia’s campus in Moorhead is situated within roughly 200 miles of over a dozen different reservations, and as a regional center for business, medical, banking and other services, Fargo-Moorhead attracts people from several different tribal backgrounds.

Native residents in town come from three major tribal backgrounds: Anishinaabe (Ojibwe), Lakota/Dakota (“Sioux”), and the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara, but at least 100 different tribes are represented. What they all have in common is that either they or their parents or grandparents were forced by the United States government to attend boarding schools intended to assimilate them into Anglo/European culture – while considered progressive in its time, we now see this process as cultural genocide. These schools intentionally tried to erase cultural identity, forcing students to dress in European-American clothing, to have their hair cut in European fashion (a major spiritual violation), and to speak only in English, which was among the most devastating requirements.

But in additional to breaking down cultural identity, the vast majority of students were subject to physical, emotional, and/or sexual assaults, which can break down any individual’s mental and physical health. Further, since victims of abuse tend to commit the same types of abuse they were subject to, abuse in the boarding schools has affected younger generations, creating an intergenerational cycle of trauma.

While some Native people have been able to find healing and regain their sense of personal and tribal identity, many are still suffering—rates of alcoholism, suicide, and abuse on reservations are quite high. Staff working in the Indian Education Programs in town see these patterns among the students and families they work with, but many barriers to healing exist in the structures of schools and social-service agencies. Our grant work, then, is focused on attempting to remove some of the barriers to care and wellness that exist, so that Native Americans in our community who need help can get what they need to move towards spiritual and physical wholeness and wellbeing.

The term reparations is defined in various ways. How do you define community-based reparations? Over the next three years, what strategies are you implementing to accomplish this?

In one sense, we are using the most basic definition of the term reparations, as it is closely related to the word repair: we are trying to clarify and better set up the services available that can repair and heal Native people, those who have suffered and continue to suffer because of the trauma caused by Indian boarding schools.

Our initial community consultants helped us determine the following goals:

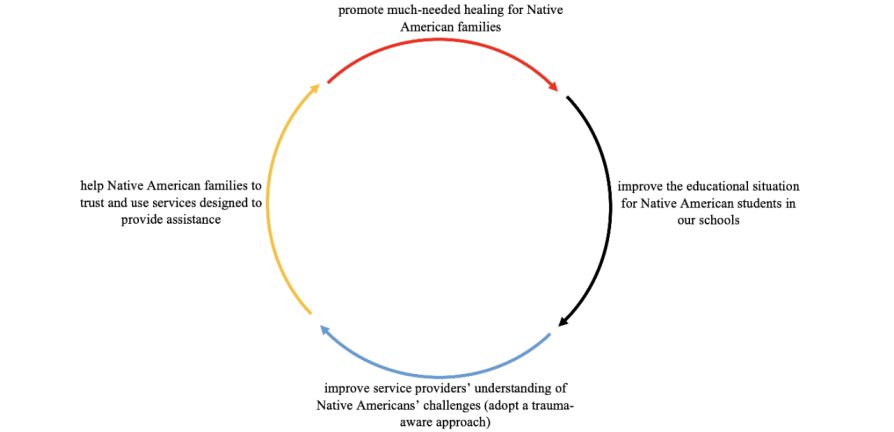

to develop a plan for community-based reparations related to generational trauma among Native Americans—trauma that was caused initially by cultural genocide in mandatory-attendance boarding schools—so that we can:

- promote much-needed healing for Native American families,

- improve the educational situation for Native American students in our schools,

- improve service providers’ understanding of Native Americans’ challenges and

- adopt a trauma-based approach in order to

- help Native American families to trust and use services designed to provide assistance.

To accomplish these goals, we plan to use community-organizing approaches – gaining information from the people who are affected, putting together training programs for teachers and social-service providers, and working with specific organizations collaboratively to help them serve their Native students or clients.

Following the traditional symbol among many tribes of the medicine wheel, we have expressed it visually in this way:

Different teams comprise different types of colleagues and partners (e.g., historians, artists, community leaders). Can you describe the composition of the Concordia Team? Moreover, who are the community partners engaged in this work?

The principal investigator is James Postema, a professor in English; he was worked with local leaders in the Native American community through a course he has taught on Native American literatures and cultures. In recent years that work has most often involved Concordia students tutoring K-12 students served by the Fargo Public Schools’ Indian Education Program, directed by Melody Staebner. Since a strong partnership with her was already in place, we asked for her help in identifying needs in the community, and she and several other community leaders put together the goals for the project outlined above.

Ricky White was chosen as our Community Fellow – he is Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) from Whitefish Bay First Nations in Ontario, Canada. Ricky has extensive experience in a variety of roles in K-12 education; he now works as a cultural trainer for schools and organizations; and he is also a powwow announcer, which means that a wide range of people see him as having the personal integrity and spiritual wisdom needed to conduct a major cultural and spiritual event.

Elijah Bender is a historian at Concordia; among other things he will coordinate interviews of our community panel members, gathering oral histories to put together a written history of ways that the Native American community in Fargo-Moorhead has worked energetically and resiliently to try to better things for themselves.

We have recruited a Community Panel composed of Native people in town who work primarily in education and social-service agencies, but who also include state legislators as well as parents of children in the local schools. They have provided enthusiastic advice and passionate determination to help us reach the goals of our grant.

What factors are important to know about your local history to better understand your project?

Concordia chose to work with the Native American community because they make up the largest minority group in this region, and because layers and layers of injustice have kept many of them in poverty, self-doubt, and cultural ignorance.

Native Americans’ situation is different from those of other groups in several ways: each reservation has its own legal status as a dependent but sovereign nation, based on the treaty which they signed with the United States government. While those treaties were rarely negotiated in good faith by government officials, they do have important status in federal law, guaranteeing various rights and services. So in this way, Indigenous people have had a long-standing—if unfulfilled—strong legal basis for equal rights.

However, each treaty is unique, so the rules and requirements for each reservation are different; and, as is widely known, the United States has not honored a single one of the hundreds of treaties it has negotiated—though often the government has used the treaties to confine Native people to their reservations. Since the 1870s, various overlapping and sometimes contradictory laws have created a complicated web of barriers to self-determination and prosperity for tribes. Native peoples have been subject to killings, forced removals, starvation, and poverty caused by broken treaties and the “legal” confiscation of over half of their land—and, of course, mandatory attendance in boarding schools. It is only in recent decades that they have been able to use the treaties to establish tribal sovereignty in some real ways.

Because Fargo-Moorhead is a community divided by state borders, and because we are not immediately near any single reservation, there is no single dominant organization or Native cultural background in town, so we have to find ways to better people’s situations using means that are appropriate for their own cultural backgrounds. We have taken care to have different backgrounds represented in our Community Panel, and the project roles have leeway built in to them to recognize this ethnic diversity.

Is there anything else you would like to our partners across the country to know about Concordia’s Democratic Futures project?

Too many Americans are quite ignorant of about the context in which Native American peoples live and work to maintain their cultural identities and, indeed, to survive. Further, what most Americans know comes from the years before 1900, when many efforts were made to record tribal mythologies, music, and narratives, under the assumption that the Indigenous cultures would soon be gone. The boarding-school era is almost completely unknown to whites, partly because survivors of the schools themselves have not wanted to talk about their experiences – for their own sakes and also so as not to burden friends and family with their personal traumas. But the silence and ignorance have not allowed healing.

Recent discoveries of children’s bodies buried on the grounds of residential Indian schools in Canada have gotten a lot of media attention, which has begun to create some awareness of the reality of boarding schools in the United States. But Native Americans are still portrayed more by ignorant stereotypes than anything else, and Native peoples have nowhere near the representation among the general public that other groups do – in government, sports, the media, or any other context. Rather, they have been represented until just recently by things such as Disney’s wildly inappropriate film Pocahontas, and team mascots of the Washington “R-words,” the Cleveland Indians, and the Atlanta Braves. Things are changing in that area, but very slowly, and it will be a long time before those mascots and other offensive images are forgotten.

At the local and regional level, we are working to combat the ignorance of Native American cultures, struggles, and trauma inflicted by the United States government with the additional goal of creating a scalable approach for future expansion.